Significance Tests within Black-Box Models: Explorations and Challenges

keywords: statistical tests, black-box tests, significant patterns

Introduction and Background

For someone with no statistical background, the most direct approach to measuring a component’s significance is to remove it from the current system and compare the resulting changes. When the potential significance is large, we can simply visually represent the observable effect through simple data visualization. This approach is particularly effective when the effect is substantial, as it is simple, effective, and highly persuasive. However, in numerous real-world applications and scientific experiments, the “effects” or “improvements” are often very small, making it difficult to make a definitive YES or NO judgment. In such cases, significance tests prove to be valuable tools. In other words, significance tests provide a logically rigorous and more finely sensitive metric, enabling the detection of more positive findings and controlling the required Type I error.

In many applications, significance tests can be roughly interpreted as: if the experimental covariate (or feature) \(\mathbf{X}\) has effect to the outcome \(Y\) given the covariates \(\mathbf{Z}\). In scientific application, the focus lies on establishing the relationship between covariate \(\mathbf{X}\) and the outcome \(Y\), while taking into account the influence of \(\mathbf{Z}\). Machine learning (ML) is also concerned with this test: whether the variable \(\mathbf{Z}\) is sufficient, in terms of \((\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Z})\), for predicting the outcome \(Y\).

Next, how should we formulate the concept of “effect”? A commonly utilized and elegant metric is conditional independence:

\[\mathbf{X} \perp Y \mid \mathbf{Z}.\]When the assumption of conditional independence holds, it is straightforward to assert that the covariate \(\mathbf{X}\) has no effect on the outcome \(Y\) given the context provided by \(\mathbf{Z}\).

However, practitioners have identified certain practical applications where they perceive the hypothesis of conditional independence to be overly restrictive. Specifically, in many real-world scenarios, the focus may shift towards assessing the value that a variable \(\mathbf{X}\) can provide to \(Y\) in specific performance criteria (which may enhance the testing power). For instance, in regression analysis, the emphasis may lie in determining whether \(\mathbf{X}\) enhances predictive accuracy in terms of the conditional expectation \(\mathbb{E}( Y \mid \mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Z})\) compared to a model relying solely on \(\mathbf{Z}\), that is, \(\mathbb{E}(Y \mid \mathbf{Z})\).

Taken together, significance tests are essential for not only facilitating scientific discoveries but also for a variety of statistical methodologies, including relationship identification, modeling, and feature selection. While the conditional independence is an elegant and widely-used hypothesis, yet there also exist numerous tests that focus on the necessary conditions of conditional independence.

The Elegance and Limitations of Significance Tests in Linear Models

For conducting significant tests, it is typical to begin by formulating a model for the data, with linear models often being the straightforward, simple, and effective choice for many scenarios. This is represented as:

\[\begin{equation} Y = \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \cdots + \beta_d X_d + \epsilon, \tag{1.1} \end{equation}\]where \(\mathbf{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) denotes the vector of linear coefficients, and \(\epsilon\) represents the error term which is independent with \(\mathbf{X}\). Under the model assumption (1.1), the conditional independence of one feature given the others is equivalent to if the linear coefficient is zero, that is,

\[X_j \perp Y \mid \mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{X}_{-j} \quad \iff \quad \beta_j = 0. \tag{1.2}\]Therefore, within linear models, (1.2) offers a direct and practical motivation for conducting significant tests: by directly performing statistical inference on the coefficient \(\beta_j\). This probably the most important strength of conducting significance tests based on linear models. Nevertheless, its primary limitation stems from the increasing inefficiency (compared with deep learning models) of the linear model assumptions in more complex data settings.

Limitations

Since reasonable data/model assumptions are crucial for most significance tests, it is essential to verify these assumptions before conducting the tests to ensure the reliability of the results based on the underlying data models. In practice, assessing the assumptions of data models can be challenging. One approach is to evaluate the prediction performance using a standard machine learning evaluation routine, such as train-test data splitting or cross-validation: training the model on the training set and evaluating it on the testing set. If the model is closer to the ground truth, it tends to deliver better prediction performance. Toward this end, let’s check the empirical performance in real applications.

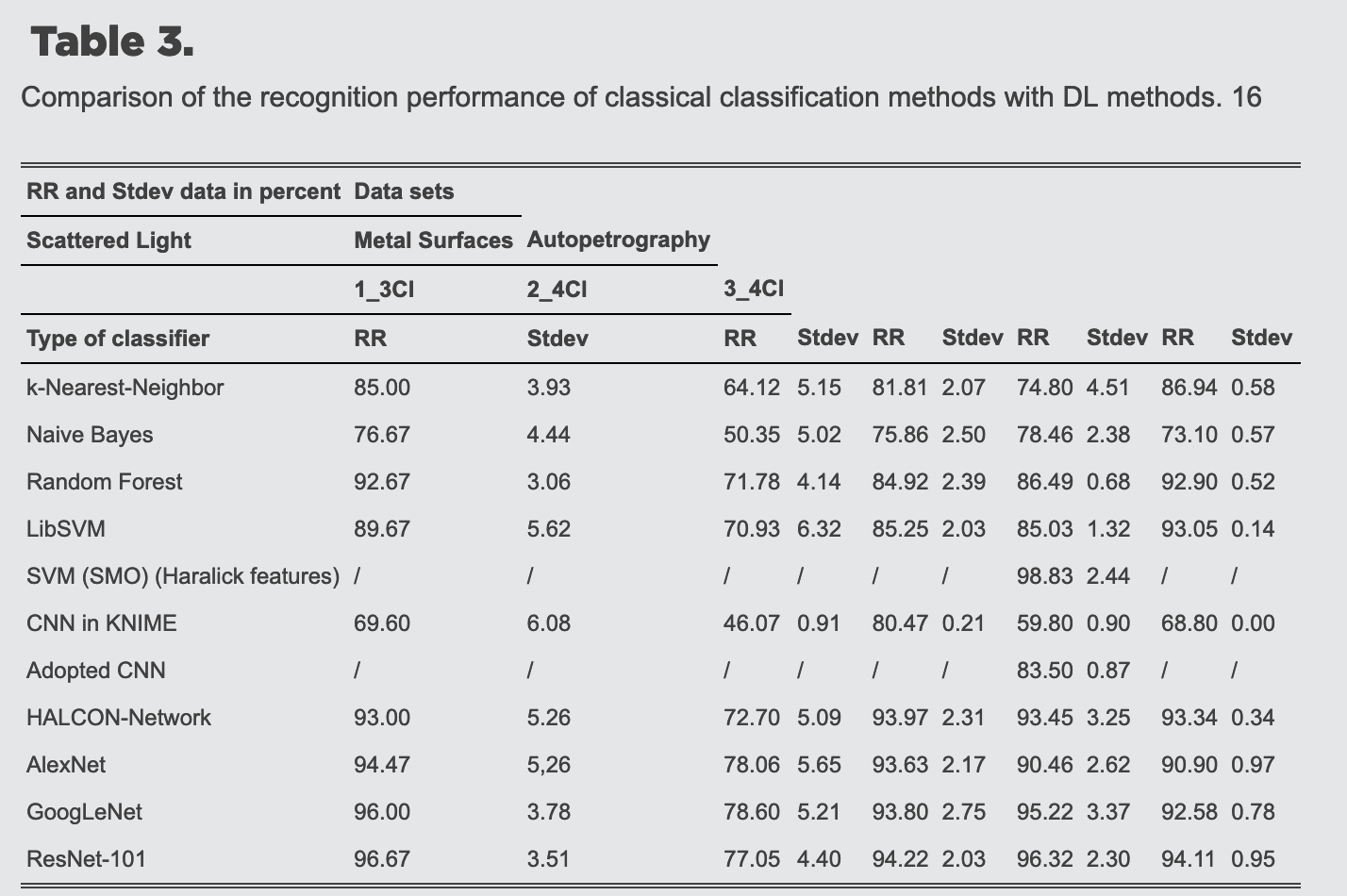

Observation 1: In complex data settings, such as industrial data and medical applications, DL models demonstrate significant numerical advantages over traditional machine learning approaches in terms of prediction performance.

This has been extensively validated by numerous experiments, with one such finding being represented here for illustration.

Anding, Katharina, et al. “Comparison of the performance of innovative deep learning and classical methods of machine learning to solve industrial recognition tasks.” Photonics and Education in Measurement Science. SPIE, 2019.

Next, we turn to the observation regarding the complexity of DL models.

Observation 2: For complex datasets, it appears that larger models (with more parameters) potentially provide better performance.

Tan, M., & Le, Q. (2019, May). Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR.

In contrast to traditional machine learning models, the empirical observations suggest that overparameterized deep learning models do not necessarily suffer from overfitting; on the contrary, models with extremely large numbers of parameters are widely used and have achieved remarkable performance in practice.

Motivated by empirical observations, a natural question arises: “Can we conduct significance tests based on DL models for data formulation?” This blog aims to provide some insights into this question.

DL: Data, Models and some Empirical Observation

Given a new nature of both data and models, in this section, we will enumerate and explain the challenges posed by this frontier in statistical tests, which will aid us in formulating a new paradigm for significance testing.

Note that this is a completely new problem, and any intuition derived from traditional statistical theory may be misleading. Instead, we probably should rely on empirical evidence and objective data-driven insights.

Nature of Black-box

DL models are often referred to as “black-box” models, likely due to two reasons. Firstly, the model is difficult to interpret or explain. In contrast to linear models, where each linear coefficient corresponds to feature importance, DL models typically contain a large number of parameters and various ad-hoc architectures, the direct correspondence between features and model parameters does not exist in large real practical models, making it challenging to explain the relationship between inputs and outcomes. Therefore, despite achieving peak performance, DL models struggle to provide reliable insights, which significantly hinders their adoption in serious applications, such as medical research and healthcare. Secondly, extremely large models with a black-box setting have become increasingly popular in real-world applications, particularly in NLP using Large Language Models (LLMs). These models are physically black-box, as they only provide outputs given inputs, without allowing access to their architecture, parameters, or training data, making it impossible or extremely costly to understand their inner workings.

Overparametrized models

This characteristic is related to the phenomenon we indicated in Observation 2. It appears that larger models consistently demonstrate better performance capabilities. Alternatively, overfitting is not as severe as we imagined for large models. This phenomenon is quite surprising for statisticians. According to classical statistical learning theory (SLT), the generalization error (which can be simply regarded as the testing error) is decomposed into approximation error and estimation error. The approximation error measures the distance between the specified functional space and the ground truth, while the estimation error qualifies the difficulty of estimating a function in the specified functional space. On this basis, larger models reduce the approximation error but increase the estimation error. Thus, this theory explains why we observe a “U” curve in the model capability versus test error plot. However, the “U” curve does not exist in deep learning (DL) models with image and text datasets, where increasing the layers or parameters does not lead to extreme degradation in performance; instead, it sometimes even improves performance.

Neyshabur, B., Li, Z., Bhojanapalli, S., LeCun, Y., & Srebro, N. (2018). Towards understanding the role of over-parametrization in generalization of neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.12076.

Even more intriguing is that the scale of DL models can grow to perfectly fit the training data, yet they still deliver impressive performance on test data. This is astonishing from a classical SLT perspective. However, whether you like it or not, overparameterized models have become the mainstream of DL models and have been proven to be remarkably effective in modern applications.

Significance of patterns

The point is attributed to the new structure of the data. In classical tabular data, a major interest is to examine the significance of features, which specifically refer to columns of tabular data (and, furthermore, correspond to some model parameters if certain model assumptions are made, as in (1.2)). This is because each instance of tabular data is well-structured, and thus, a feature is well-aligned across all instances. However, this property does not exist in more complex data settings.

For example, in image data, “background” and “object” pixels can be located anywhere in the image; similarly, in text data, important words can occur anywhere in the sentence. Therefore, formulating significance tests based on feature columns or locations, may not be entirely sensible. A more reasonable approach seems to be specifying particular patterns; then, we can examine the significance of patterns through hypothesis testing, where the null hypothesis can be formulated as:

\[\mathbf{X}_{S(\mathbf{X})} \perp Y \mid \mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{X}_{-S(\mathbf{X})}, \tag{2.2}\]where \(S(\mathbf{X})\) is a “pattern” which provided based on \(\mathbf{X}\). We then illustrate this concept through the following two examples. Note that \(\mathbf{Z}\) can be generated by {removing / permuting / replacing independent noise} of \(S(\mathbf{X})\) in \(\mathbf{X}\), since equation (2.2) remains valid under these operations.

Note that \(\mathbf{Z}\) can be generated by {removing / permuting / replacing by independent noise } \(S(\mathbf{X})\) from \(\mathbf{X}\), since (2.2) is continued to be hold for those operating.

Demostrative images in FER2013 (Facial Expression Recognition 2013) dataset.

Example 1. The FER2013 (Facial Expression Recognition 2013) dataset comprises images with categorical labels describing the emotion of the individual depicted. Specifically, the dataset consists of 48×48 pixel grayscale images, categorized into seven distinct emotions: Angry, Disgust, Fear, Happy, Sad, Surprise, and Neutral. By using some mature neural networks, such as VGG and ResNet, a prediction accuracy of >=70% can be achieved, see Leaderboard.

A sensible hypothesis based on this dataset could be if the mouth region makes a significant contribution to the prediction of facial emotions.

Example 2. The SST-2 (Stanford Sentiment Treebank) dataset comprises 11,855 single sentences extracted from movie reviews, with each phrase annotated as either negative or positive. By using BERT-like models, a prediction accuracy of >=96% can be achieved, see Leaderboard.

A sensible hypothesis based on this dataset could be that the removal of stop words does not significantly impact sentiment prediction.

Therefore, under the new formulation with significance of patterns in (2.2), we can observe substantial potential for conducting significance tests by integrating techniques from image and text segmentation, localization, and skeleton detection.

Remark. Additionally, I also had a very interesting observation for linear model assumption on image datasets. As is commonly known, in most image tasks, particularly those involving high-resolution images, the effect of a single pixel is essentially zero or negligible. This implies that equation (2.1) holds true for any single pixel \(j\). Consequently, if we formulate image data using the linear model (1.1), we can conclude that \(\beta_j = 0\) for all \(j\). According to the equivalence indicated in (1.2), this leads to \(Y = \epsilon\), which is clearly incorrect. This observation further suggests that the linear assumption is inappropriate for image data.

Formulation based on Empirical Evidence

As indicated in the previous section, we observed that DL models exhibit some experimental phenomena that are fundamentally different from those of parametrized models, and they may hold enormous potential in significance testing. Thus, let us provisionally accept (2.2) as our hypothesis test and explore the challenges that we are likely to encounter.

First, as demonstrated by Lemma 1 in

Then, the equivalent hypothesis is as follows.

Lemma 1

. The conditional independence (2.2) is equivalent to: \begin{equation} R^* := \min_p R( p ) = \min_q R_S( q ) =: R_S^*, \nonumber \end{equation} where \(p\) and \(q\) are measurable conditional probabilites of \(Y \lvert \mathbf{X}\) and \(Y \lvert \mathbf{Z}\), respectively.

Lemma 1 successfully transforms the conditional independence test into a comparison between two metrics. An intuitive interpretation is that \(R^*\) represents the optimal likelihood score attainable using the full feature set \(\mathbf{X}\), while \(R^*_S\) denotes the optimal likelihood score achievable using the subset of features \(\mathbf{Z}\). If these two quantities are equal, it implies that the subset of features \(\mathbf{Z}\) captures all the relevant information for modeling \(Y\).

Note. Here, we assume that \(\mathbf{Z}\) is a sub-feature of \(\mathbf{X}\), if not, we can append \(\mathbf{Z}\) and \(\mathbf{X}\) together as a new \(\mathbf{X}\).

Remark. Lemma 1 in

provides results for a general risk invariance test. As mentioned in the previous section, conditional independence may be too strong. In this case, other loss functions can be used, such as the L2 loss if we are interested in the different between \(\mathbb{E}(Y \mid \mathbf{X})\) and \(\mathbb{E}(Y \mid \mathbf{Z})\).

Next, we naturally require estimates of \(R^*\) and \(R^*_{S}\). A direct approach is to find the optimal \(\hat{p}_n\) and \(\hat{q}_n\) through empirical risk minimization (ERM) of \(R\) and \(R_{S}\):

\[\hat{p}_n = \text{argmin}_{p} - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \log p(y_i \mid \mathbf{x}_i), \quad \hat{q}_n = \text{argmin}_{q} - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \log p(y_i \mid \mathbf{z}_i),\]and then empirically evaluate them.

A natural question that arises is whether sample splitting is necessary. If not, we can simply evaluate the estimators \(\hat{p}_n\) and \(\hat{q}_n\) using the training data \((\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{z}_i, y_i)\), analogous to the LRT. If yes, an additional testing / inference set is required to assess the performance of \(\hat{p}_n\) and \(\hat{q}_n\).

The following figure in

Zhang, C., Bengio, S., Hardt, M., Recht, B., & Vinyals, O. (2021). Understanding deep learning (still) requires rethinking generalization. Communications of the ACM, 64(3), 107-115.

Therefore, the most practical reasonable solution is: split data as estimation and inference parts, estimate \(\hat{p}_n\) and \(\hat{q}_n\) from estimation dataset (index set \(\mathcal{I}\) with size \(n\)), and evaluate them in an independent inference dataset (index set \(\mathcal{J}\) with size \(m\)):

\[T_{n,m} = \hat{R}_m(\hat{p}_n) - \hat{R}_{S,m}(\hat{q}_n) \quad \to \quad R^* - R_S^*.\]Our main idea is to use the left side (an empirical metric, we can get) to estimate the right side (the population metric, we want to infer). Additionally, we need to consider its asymptotic distribution. To proceed, we can decompose the empirical metric as follows:

\[\begin{align*} T_{n,m} & = \underbrace{\hat{R}_m(\hat{p}_n) - R(\hat{p}_n) + R_S(\hat{q}_n) - \hat{R}_{S,m}(\hat{q}_n)}_{T_1} \\ & + \underbrace{ R(\hat{p}_n) - R^* + R^*_S - R_S(\hat{q}_n)}_{T_2} + \underbrace{R^* - R_S^*}_{T_3} \tag{3.2} \end{align*}\]The motivation for this decomposition is straightforward: to establish a connection with the population by adding and subtracting terms from the empirical metric. Under the decomposition given in (3.2), we can decompose \(T_{n,m}\) into \(T_1\), \(T_2\), and \(T_3\) components, and we will examine each term separately.

- \(T_1\) is a conditional i.i.d. average.

where \(\Delta_{n,j} = l \big(y_j, \hat{p}_n(\mathbf{x}_j) \big) - l \big(y_j, \hat{q}_n(\mathbf{z}_j) \big)\) is the differenced evaluation of \(\hat{p}_n\) and \(\hat{q}_n\) based on testing sample \((\mathbf{x}_j, \mathbf{z}_j, y_j)\). \(T_1\) seems is a triangular array with the typical conditional iid average, and by invoking the central limit theorem for triangular arrays (see Corollary 9.5.11 in

- \(T_2\) converges to zero in probability.

The term \(T_2\) represents the standard excess risk for ERM, and it can be shown that \(T_2\) converges to zero in probability. Existing results also have established the convergence rate with order \(\gamma > 0\) of \(T_2\). These results typically require that the ground-truth satisfies certain regularity conditions, such as smoothness, but unfortunately, these conditions are often impossible to verify. Yet, most importantly, we have observed that DL has delivered exceptionally good performance in practice, make it more reliable than classical model assumptions. We roughly believe that this condition is reasonable, at least for those models that exhibit excellent performance, but the exact value of \(\gamma\) is unknown in practice. However, it must be acknowledged that this condition is difficult to verify.

- \(T_3 = 0\) under the null hypothesis.

The term \(T_3 = R^* - R_S^*\) is the simplest, which equals zero under the null hypothesis.

So far, everything appears to be proceeding smoothly. Specifically, \(T_1\) follows a normal distribution, \(T_2\) converges to zero in probability, and \(T_3\) equals zero under the null hypothesis. Hence, let’s standardize \(T_{n,m}\) by the standard deviation (sd) of \(T_1\), and we anticipate that it will follow a standard normal distribution \(N(0,1)\).

However, unfortunately, it does not conform to our expectations. Specifically, the normalized \(T_{n,m}\) is written as follows.

\[\widetilde{T}_{n,m} = \frac{\sqrt{m}}{\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}} T_1 + \frac{\sqrt{m}}{\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}} T_2 + \frac{\sqrt{m}}{\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}} T_3,\]where \(\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}\) is a sample standard deviation of differenced evaluations on the inference set, that is, \(\Delta_{n,j}\) for \(j \in \mathcal{J}\) conditional on \(\hat{p}_n\) and \(\hat{q}_n\) are given.

Next, we will discuss three very interesting phenomenon and issues of \(\widetilde{T}_{n,m}\) below.

Dirac-mass, Bias-sd Ratio and Sample-splitting Ratio

Firstly, an unusual phenomenon: \(T_1\) may degenerate into a Dirac mass under certain circumstances. For example, under the null hypothesis \(H_0\), we have \(p^* = p_{Y \mid \mathbf{X}} = p_{Y \mid \mathbf{Z}} = q^*.\) Hence, under some conditions,

\[\hat{p}_n \to p^*, \quad \hat{q}_n \to p^*, \quad n \to \infty, \quad \text{in probability}.\]On this ground, \(\Delta_{n,j} = l_j(\hat{p}_n) - l_j(\hat{q}_n) \to 0\) for all \(j \in \mathcal{J}\) and \(\hat{\sigma}^2_{n,m} \to 0\) in prob. Thus, we find that, under the null hypothesis \(H_0\), \(T_1\) degenerates into a Dirac-mass at 0. Such a result appears to violate the conditions of the triangular array CLT, as it typically requires that \(\hat{\sigma}^2_{n,m} \to \sigma^2 > 0\) in prob (see Corollary 9.5.11 in

Furthermore, this phenomenon also gives rise to two issues concerning \(T_2\).

- Bias-sd Ratio

Based on the previous discussion, let’s assume \(T_2 = O_P(n^{-\gamma})\), then the normalized \(T_2\):

\[\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}} T_2 = O_P( \frac{\sqrt{m} n^{-\gamma}}{\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}}).\]Since \(T_2\) itself represents a certain bias of the non-parametric model under finite samples, and then is normalized by the standard deviation, we refer to this term as the bias-sd ratio. Since \(\hat{\sigma}_{n,m} = o_P(1)\) and \(\gamma\) is unknown, it is entirely possible that the bias-sd ratio does not converge to zero in probability. Therefore, this introduces an unestimable nonvanishing bias-sd ratio into the null distribution \(N(0,1)\) in our initial expectation.

- Sample-splitting Ratio

Additionally, another key observation is that the sample-splitting ratio, namely the ratio of \(n\) to \(m\), has a significant impact on the convergence of the bias-sd ratio. This finding is consistent with empirical evidence, as it is often observed that changing the sample-splitting ratio can lead to drastically different results.

A safe choice is to make \(n\) as large as possible, thereby ensuring that the bias-sd ratio vanishes. However, provided that the correctness of the test is ensured, we prefer \(m\) to be as large as possible to increase the power. Therefore, a dilemma arises: the power of this test statistic is determined by \(m\), how to tradeoff the sample-splitting ratio, so that we maximize the test power while maintaining test validity.

- Summary

Therefore, if we follow the previous idea to construct a test statistic similar to the LRT with a normal null distribution, we need to address the following questions.

- How can we establish a results for CLT when \(\hat{\sigma}_{n,m}\) vanishes in probability? or find the correct scale of the variance in a finite-sample situation.

- When \(\gamma\) is unknown, how can we guarantee that the bias-sd ratio converges to zero in probability?

- What is a reasonable sample-splitting ratio that ensures an asymptotic distribution and maximize the testing power?

Ending

This blog post aims to introduce some background and challenges of black-box tests, presenting a straightforward and intuitive idea to tackle them. The content primarily recaps the exploration and process of our paper

The primary goal is to “cast a brick to attract jade,” sparking a thought-provoking discussion that will hopefully inspire more brilliant minds to get involved.

Of course, this approach/framework (constructing a LRT-like test; the null distribution from CLT) is not the only way to solve black-box tests, and it also has its limitations. Typically, we currently only obtain asymptotically valid tests, which means that the p-value is correct only when \(n\) approaches infinity. Yet, it appears that even obtaining asymptotically valid tests is not easy at all.

Other approaches I personally appreciate is the purely nonparametric tests framework (similar to permutation tests), which includes the Conditional Randomization Test (CRT;

Furthermore, there are some important references, including but not limited to